Hello, dear reader; it has been seven months since my last article on Why Log Returns. This time, I am doing some introspection on guiding principles that have helped me grow as a machine learning engineer. Such introspections will usually rot in my private notes, but I hope there will be some value in sharing this time. Many of these ideas originate from others through their writeups and speeches, and I am immensely grateful for their willingness to share.

In no specific order, the principles are:

- Embrace Checklists

- F*ck and Unf*ck

- Acknowledge Alternatives

- Communicate Often

- Observe and Document

- One Change at a Time

- Embrace Checkpoints

- Be Generous

- Know the Data and Its Transforms

- Embrace Constraints

Before diving in, I would like to point out that a more fitting title for this article would have been something like “Some Principles that Guide My Work as a Machine Learning Engineer,” but that did not sound as catchy to me. As I will expand on later in this article, placing a constraint of ten also helped me approach this piece with a clearer mind.

Embrace Checklists

Wikipedia defines a checklist as a type of job aid used in repetitive tasks to reduce failure by compensating for potential limits of human memory and attention. I think that is a great way to put it, especially the bit about compensating for limits of human memory and attention.

Machine learning engineering is a very iterative endeavour, so there are many cases where new tasks pop up as you do the work. For example, if the model doesn’t perform well, you may need to try a different feature engineering or modelling approach. As a result, you may need to update some other part of the system to align with that change, and such modifications are easy to forget.

There was a time when I did not regard checklists highly. What used to happen was that I would remember that some change was necessary, but then something else would pop up, after which I would completely forget to make the change. The reminders would often come at the least desirable times, such as when something crashed or the data pipeline got corrupted.

The story is much different now. I have a checklist for almost everything, whether technical or non-technical. A checklist is very beneficial because it is a tool for keeping track of what I need to do. Before I can say that a task is done, I go through the list and ensure everything is checked or make the conscious decision—acknowledging potential consequences, too—not to do one of the items.

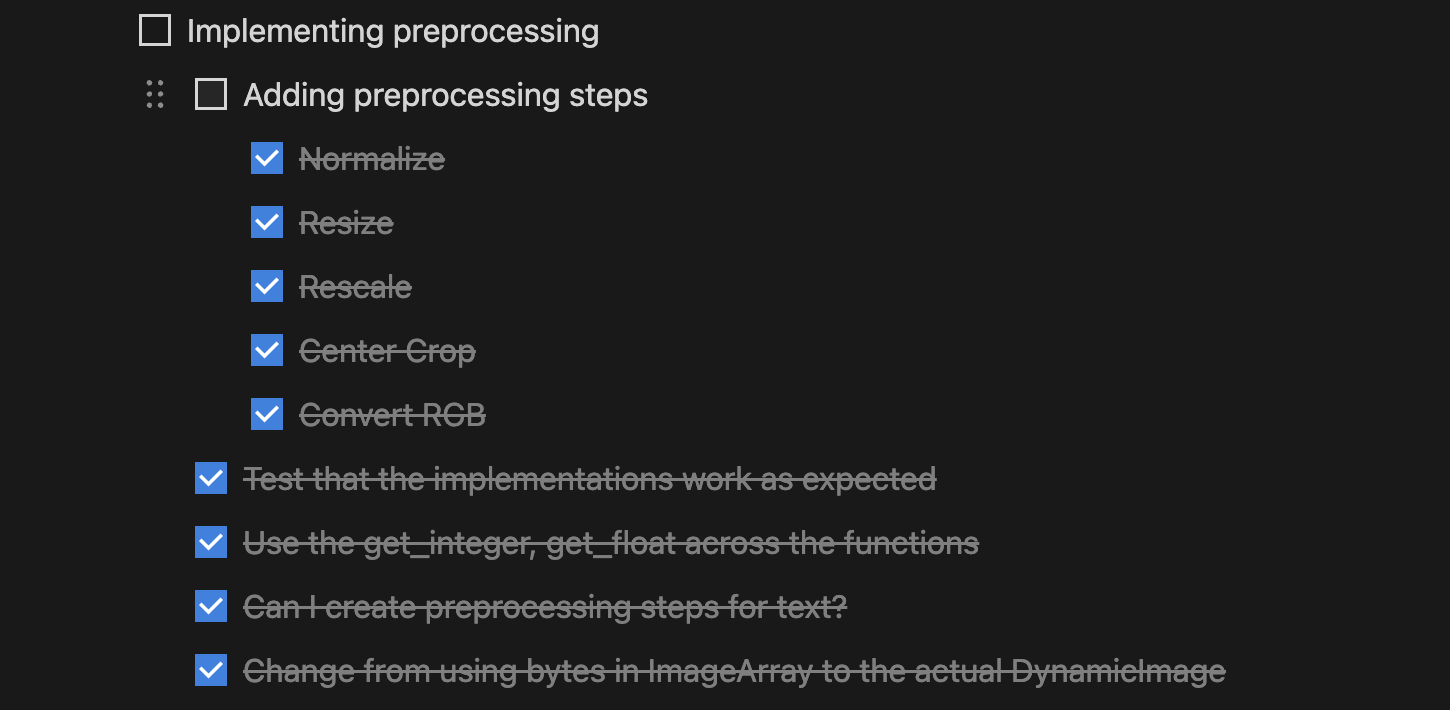

Here is a screenshot of one of my checklists when working on Ahnlich.

My approach to creating a checklist is to define my approach to achieving the task; then, I make the requisite actions or desired attributes of the end goal into entries on the list. If you look at the list sample above, you will see that the list is also nested; this is because I think about the actions necessary for each action until I don’t feel any uneasiness about how to accomplish an item.

That leads to another benefit of using checklists: it exposes my lack of clarity about achieving a task more concretely. My inability to create a checklist often indicates that I need a clearer picture of accomplishing a task. Since I have it written, not just fuzzy in my head, I feel the freedom to ask questions, seek contributions from colleagues, and do the necessary research to get me to the point of more comfort and clarity.

In Claude Shannon’s speech on Creative Thinking, he said: “Suppose you have your problem here and a solution here. You may have too big a jump to take. What you can try to do is to break down that jump into a large number of small jumps.”

The Checklist is my tool for achieving this.

F*ck and Unf*ck

Sorry to have swear words in this article already. This idea is something I picked up from Tim Ferriss’s book Tools of Titans. Sadly, I don’t remember which of the guests said it, but it goes something like:

When writing a piece, I am not scared of putting swear words in there or having the first version look like an eyesore. The objective is to ensure that the piece exists, i.e., f*cking my way to completion, after which I must unf*ck it and get it in the best version possible. The work is not done until I am done unf*cking the piece.

I messed up the narration, but I will do a proper attribution when I re-read the book (which should be soon).

The concept of f*ck and unf*ck flows nicely from that of using checklists; it is a nice tool for when a checklist doesn’t cut it. As Abraham Maslow wrote in 1966, “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

Machine learning engineering often involves moving in the dark, sometimes with many unanswered questions, knowledge gaps, and little clarity. When this happens, there will usually be a more generic next step, and you must work your way to precision via action and trying things out. Let’s say you need to deploy a model in a new environment, and you don’t know the platform-specific terminologies or where the tooling is, and there is a bunch of documentation to go through.

F*ck in this situation would be akin to doing some of the following:

- skimming through the docs for the most relevant instructions

- using default configurations

- finding a template either from the docs or another codebase to gain more understanding

- iteratively modifying things till it works

Unf*ck in this situation would be akin to doing some of the following:

- using the setup that works as a guide to finding more specific parts of the docs

- understanding what the default configurations mean and fitting them to the current task

- asking more concrete questions from knowledgeable engineers

- testing that it not only works but works as expected, is resource efficient and secure

F*ck and unf*ck is about opening up to a lot less structure at the start to gain momentum and an initial win, then applying discipline after to get the work to shine. It pushes me to get things to work, knowing that the software is far from finished. After this, I work backwards, cleaning up and optimising things to ensure they are properly done. I must admit that there is a tendency not to unf*ck things due to tight timelines or laziness; it often takes a disdain for mediocre work and some discipline to overcome that inclination.

Acknowledge Alternatives

Many mental models, from the risk-reward framework to the opportunity cost model, have the concept of alternatives at their core. There is a centuries-old proverb that goes, “There is more than one way to skin a cat.” If I were to extend this, I would say, “But some ways are better than others.”

When faced with a situation, there is a tendency to go with what first comes to mind instead of thinking for slightly longer and choosing a better fit. This inclination applies both to problems—there can be value in redefining them or choosing a different one—and to solutions. The cost of not taking some time to think about this and making the wrong choice is that path dependence may come into play; invested resources may not yield desirable outcomes. That you think of alternatives does not eliminate making a less optimal decision, but at least you tried.

I often try to get my teammates involved in deciding between alternatives. As for problems, this can help me quickly find out if a problem is worth solving in the first place, if someone has already solved it, or if I am thinking of it the wrong way. As for solutions, researching the right one for the scenario and getting frequent feedback from my team on things like design or library choices can be invaluable.

Acknowledging alternatives can have a downside. You do not want to consider the tens or hundreds of options available for all situations, as this will quickly lead to decision fatigue. At a deeper level, thinking of alternatives comes down to developing awareness that makes one mindful enough to take a step back and gain a better view of the situation and its possible approaches.

Communicate Often

There are hundreds of pages on the internet discussing communication, but I still had to include it in this article. The key point here is that it is not just about communicating but doing it often, not only from the angle of telling but also from asking and seeking updates. An engineer needs to be involved in the push-pull process of information flow.

The importance of communication in a complex project cannot be overemphasised; it is usually the primary means through which contributors understand what is going on. Every engineering task builds on the knowledge of the project’s state, so when things change, those developments must be known to avoid efforts in the wrong direction. When I say “things change” here, it could vary from the approach to a problem needing to differ from what was initially discussed to the problem no longer requiring a solution. If a change impacts someone else’s work or perception of the work, it should be communicated.

The most infuriating times for me are when I am working and thinking based on stale knowledge; something has changed, and someone has not passed that information on. I also feel very uncomfortable when there is a new development and my colleagues do not know about it yet.

I like to use various approaches to share information, such as messaging the affected individuals via private chat, shared channels, or setting up a call; the choice depends on the scenario. I also find that standups enable communication. My issue with relying on standups mainly to transmit information is that they are not always daily; you should not wait days to say what you need to say. Also, standups are often team-based and may only cater to some of the colleagues that you work with; others may be on a different team or even in a different organisation.

Observe and Document

Observation is a crucial skill for scientists and engineers; it serves as a foundation for many other activities, such as asking questions, seeking improvement, learning from others, and coming up with new ideas.

Reading—more like listening to, I do audiobooks—The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators made this sink in further. I have become more mindful about observing what is happening during calls, on projects and within my teams. I often look closely to get a good picture of the processes that make things work, how engineers who inspire me do their work, and the philosophy (the why) behind various decisions.

It is easier to spot interesting things when you have some expectation of the entity being observed. For example, if a pricing model is being trained and you expect to see a linear regression model but find that a decision tree is being used. That makes you go: “oh, but why?”, but if you do not even know what it means to train a model model, you would likely not be able to make that observation. When expectations do not exist, it is still possible to observe, but it will be from the perspective of learning alone.

As for documenting things, writing, be it actual notes, short points, or sketches, is incredibly beneficial. While I have a good memory, I often forget things I do not expect to forget. Writing things down ensures I have something to return to without panicking when that happens. Documenting things has benefited me in so many ways, but one of my favourite benefits is that it makes it easy for me to do some retrospection. For example, if I want to think of ways to improve a system or process, it is easier to have a document containing my observations and start from there.

Why do I have “observe and document” as one point?

The issue with observing is that it is often a passive activity. It is hard to do, especially when your mind is yet to be fully engaged with the item to be observed. This is where writing comes in. In the process of putting things down, my false assumptions or expectations jump at me. Many times, when I am documenting a process, I see myself going, “Oh, this is surprising,” which ends up being an observation.

So which comes first, the observation or the documentation?

My answer is that it depends: If I am able to start observing without writing anything down at the start, I then go ahead and write down the things I notice. If I am unable to do this, perhaps because of a lack of full attention, I simply start writing things down, and then observation follows.

One Change at a Time

I believe every machine learning engineer will learn the concept of changing one thing at a time, either from experience or through a resource—as you will in some minutes if you did not know of it previously. My first encounter with this idea in writing was through the book 9 Rules of Debugging, and it has stuck ever since. The principle is pretty simple: change one thing, then test to see if it works or how it works.

When debugging, some scenarios require changing various parts of your code to see if they will fix the error or reveal the root cause. The idea with changing one thing at a time in this context is that you should be able to tell the effects of your changes, especially concerning getting a fix in. Contrast testing one change at a time (reverting if it does not help) with testing only after making five changes (none of those changes helps fix the issue); you will find out that the latter messes things up quite quickly.

During the implementation of machine learning algorithms is another context where one change at a time helps a lot. Machine Learning algorithms are notorious for having silent failures, so the code does not break, but the outputs are wrong and you can’t say why unless you dig deep and try to understand the data. Making one change at a time and looking into the results helps you understand the data flows much better. If you do not make iterative changes, it gets harder to tell if the results are correct.

In a slightly different context, imagine you have an existing model and want to improve it. The recommended approach is to change one variable in the model or training process and then evaluate the model to see how it performs in response to your modifications.

If you really really know what you are doing, it may be okay not to stick to the one-change-at-a-time principle. However, you should know that you may be shooting yourself in the foot.

Embrace Checkpoints

As a machine learning engineer, I have run quite a number of scripts that take days to complete. Hence, I can tell from experience that “Anything that can go wrong will go wrong.” There are so many reasons why a script can go off the rails: a wrong transformation, a terminated Linux process, wrong configurations, connectivity issues, files being corrupted, models starting to overfit, etc.

There are various ways to limit the impact of such unpleasant surprises, but having checkpoints at different points in the data transformation pipeline is my favourite. Doing this comes with various benefits, such as resuming processes from the last stable state and using saved outputs for analysis and debugging if something seems off.

The approach to checkpointing will depend on the context; some tasks will have checkpointing functionality that is easily accessible, while others will require you to write more substantial amounts of code. For example, when training a model, PyTorch makes it easy to set up checkpointing of model weights, but writing a custom data processing script may require you to handle checkpointing yourself. Remember to clean up the checkpoints when they no longer provide any value, keeping them around as the files can add up quickly and consume a lot of storage.

Sometimes, I feel lazy; I want to get the process running and be on my way, having to think about checkpoints. In many cases, being lazy in such a manner has come back to bite me in the butt. Now, I simply set up checkpointing and give myself peace of mind, knowing that I do not have to start afresh if something goes wrong.

Be Generous

I was not sure what to call this section, but “Be Generous” seems to do the job. This is a phrase I learned from the book Never Eat Alone. However, I would like to think that the mindset is one that I already had and lived by way before reading the book—there is something awesome about being able to put a word to something.

There is only a little to say about this besides what it says. Do not just be fixated on yourself and getting your tickets done. There is value in raising your head to see who needs some assistance or trying to understand how you can provide value to someone, which does not exactly come down to closing tickets. I have some time in the week dedicated to doing this, looking around to see what others are up to and thinking about how I can help.

There is a social side to this, in that you build a better connection with the person and also get fulfilment from them achieving their goal with some contribution from you. I cannot speak for others, but I feel very good when I remember times when I offered to help understand an issue someone was facing, and we came up with a fix. In many cases, it turns out to be a basis for building that relationship.

There is also a development side to this: you get to see what others are working on and can learn from getting involved or even just thinking about a diverse set of challenges. Often, I find myself learning about a new technology, pushing to understand certain concepts better, and revising the fundamentals simply by trying to help.

Being generous does not have to be down to writing code alone or fixing bug issues alone; it also includes things like:

- volunteering at conferences

- offering career advice when a friend feels stuck

- giving talks

- sharing lessons and experiences

- writing articles

- referring people you have confidence in

- reviewing people’s documents or write ups

I would like to mention that being generous does not include stretching yourself too thin so that you are unable to do the things that are important to you well. Do what you can, and that suffices; it is not an obligation.

Know the Data and Its Transforms

As a machine learning engineer, you will often be the one with knowledge of how the system works end to end. This often means knowing how the data:

- gets into the data store

- gets pulled out and is transformed into features

- gets used to train and evaluate the model

- is being processed before and after inference

- is being utilised for monitoring purposes

Hence, it is essential to understand the nature of the data. One way to go about this is to spend some time combing through the data, making generalisations about its attributes and what it should look like. You can also use descriptive statistics to get a sense of the data, its main features, variability, distribution, outliers, etc. The benefit of having this kind of feel for the data is that you can have some intuition about whether the data is off based on the business context.

The same idea applies to knowing the transforms the data passes through. When working on a project that spans multiple teams, it is not uncommon to find duplicate transforms or even erroneous ones at various points of the pipeline. Knowing the transforms also makes it possible to collaborate fruitfully with the scientists. You will be in a good place to spot expensive transforms that need optimisation or are impossible to integrate due to various system constraints.

I once worked on a project, specifically on the data pipelines side of things. At a certain section it was fine to have duplicates—based on the id—in which case we would drop them, keeping only one copy and everything else happens as usual. However, in this scenario I observed more duplicates than usual, tracked it back to potential sources that looked suspect and thought of possible solutions to the issues I found. I raised the question with the scientist I was collaborating with who then checked as well, concurred with my findings and went with one of the suggested solutions. The code did not break and it was going to work as usual, but if I did not understand the data, it would have been nearly impossible to observe that something was wrong.

Embrace Constraints

At the start of this piece, I mentioned needing to constrain the number of points I would write about to get myself to do the work. So here is point ten: embrace constraints.

In a world that puts endless options in our faces, one can easily lose the structure that is beneficial for doing great work. It is said that constraints help increase creativity, so I am in the camp that preaches that we should actively pursue constraints. Life in itself has constraints; you can’t live forever, you can’t have infinite money, and you can’t work on all projects. Hence, if you are doing a project or task without constraints, you should look deeper, and you will find them; if you don’t find any, make one.

There is a thin line between constraints being of positive or negative value. Constraints should be questioned and pushed against periodically, not just accepted or inherited without any context, enough of being philosophical and back to machine learning talk.

One constraint that will likely piss you off in machine learning—especially if you have an engineering background—is that the predictions will not always be correct, and the generated artefacts can suck on some inputs. I struggled with this at the start of learning the fundamentals, and I had to accept it as part of the nature of machine learning algorithms. Instead of shying away, I made room for such failures in the machine learning systems I built.

Another constraint is that the super cool models require heavy computing resources. Social media might be buzzing with how this model is the best thing since sliced bread. You then try to run it on 100,000 documents only to find it may take a week to complete. Then you realise that machine learning is expensive, and you need to make a trade-off between the time and cost to run.

I can go on and on about the various constraints in the field, but my point here is that constraints should not cause you to give up. Instead, you should find a way to balance things out and make it work. It is also important to communicate the constraints with the necessary stakeholders in the project so everybody is on the same page.

Conclusion

In this article, I wrote about some principles that have guided my machine learning engineering career. I intend to improve at applying them while picking up other beneficial principles as I learn and grow. Every single point on this list has been useful to me, from embracing checklists to embracing constraints. No, they are not easy to adopt; it takes time and conscious application.

This article was difficult to write, but I hope it was much easier to read and that I could clearly communicate my thoughts. Thank you for reading some or all of it. It is my wish that you find these tips beneficial in your life and career or, at the very least, become aware of them and start becoming more mindful.

I will now go ahead and write a couple more pieces. They are about my contributions to Ahnlich, an in-memory vector database written in Rust, which some friends and I worked on this year. I picked up the language to help build it, and it was a great experience.

See you there.

Leave a comment