Hello dear reader, my friends and I have been building an in-memory vector database, which we are calling “Ahnlich”, the German equivalent of the word “similar”. Our goal is to give developers a means to easily integrate semantic search and key-value retrieval functionalities in their systems.

We have been working on Ahnlich for a significant part of this year, recently doing an alpha release. The core team currently consists of five contributors, doing a wide range of things such as building the database, working on the embedding service, working on demos via the Python client, etc.

The team is hoping that we can learn from the process of building this and create a suite of tools that can serve production use cases. The team also believes it will be more fun to collaborate with you if you could contribute to Ahnlich.

The purpose of this article is to tell you about this project, and I am hoping that one or all of the following happens at the end:

- You feel inspired to contribute or use it in your side projects.

- You share the piece, and someone else feels inspired to contribute or use it in their side projects.

- You learn from the knowledge shared here.

- You are simply aware of its existence.

Now let me get into the actual job of writing this article.

I will start by writing a bit on lexical search, which is the traditional way of doing information retrieval, then “semantic search” and “in-memory vector database”, two keywords I used earlier in this article, after which I will proceed to the rest of the piece. In other words, if you already know what they mean, you can skip to the “What is Ahnlich?” section.

Here is the outline:

- What is Lexical Search?

- What is Semantic Search?

- What is an In-memory Database?

- What is Ahnlich?

- Why Build Ahnlich?

- What is Next?

- My Ask

What is Lexical Search?

Before I talk about what semantic search is, I would briefly talk about what came before it: lexical search. Lexical search is the traditional way of finding relevant information, and this is not to say it is now outdated; it is still as essential today as it was years ago. However, semantic search complements it, significantly enhancing the quality of information retrieval systems.

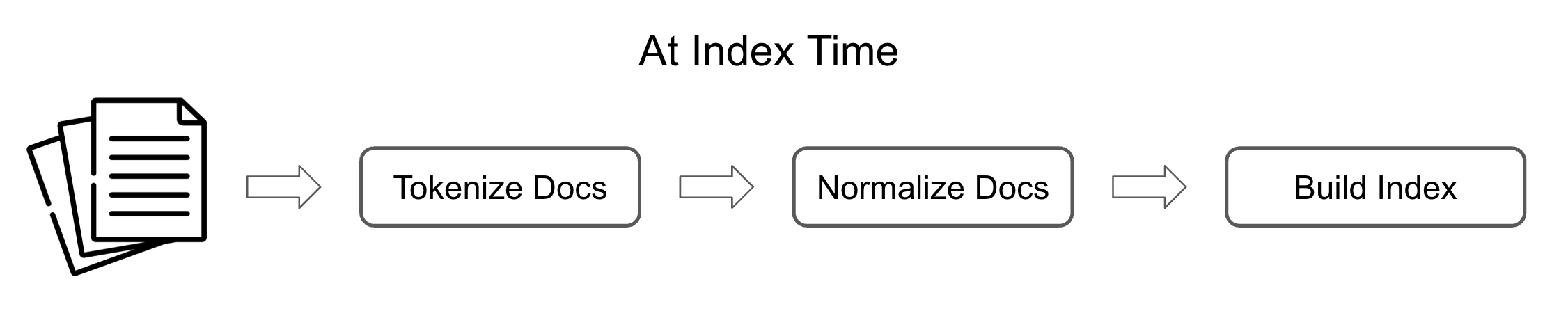

A simple approach to preparing for lexical search is to create an index by doing the following on all documents with which you intend to make an index:

- Tokenization: This means you split the document into individual terms. So if you have a document that says, “The lights are looking so beautiful this evening”, you split this into [“The”, “lights”, “are”, “looking”, “so”, “beautiful”, “this”, “evening”].

- Normalize the terms: There are various normalization approaches possible, but the common ones are lowercasing, lemmatization, or stemming (depending on the context). Doing this means the tokenized values become [“the”, “light”, “be”, “look”, “so”, “beautiful”, “this”, “evening”].

- Build an inverted index: An inverted index is a data structure—commonly referred to as a posting list—that maps each unique word to the ID of the documents it appears in. This means you have something like: {“the”: [0], “light”: [0], “be”: [0], “look”: [0], “so”: [0], “beautiful”: [0], “this”: [0], “evening”: [0]}. An inverted index is often more complicated, but this explanation suffices.

A simple approach to doing lexical search at query time is to do the following:

- Repeat the preprocessing done at index time on the query: This means that you repeat the first two steps from the indexing phase. If you have a query that says, “Are the lights on now?” you will end up with tokenized values like: [“be”, “the”, “light”, “on”, “now”]

- Run a relevance scoring algorithm on the index: There are many ways to calculate the relevance score; in this case, I will use the boolean model, which just means I give a score of one to each document for each query term that appears in it. Following the example, the document with id 0 gets a score of 3 because [“be”, “the”, “light”] all appear in it.

Now, lexical search can be more complex than I described above. There are a lot of things that can be done to make it more robust, such as removing stop words, using Best Match 25 (BM25) as the scoring algorithm, etc. However, the following explanation shows a challenge that lexical search approaches always face.

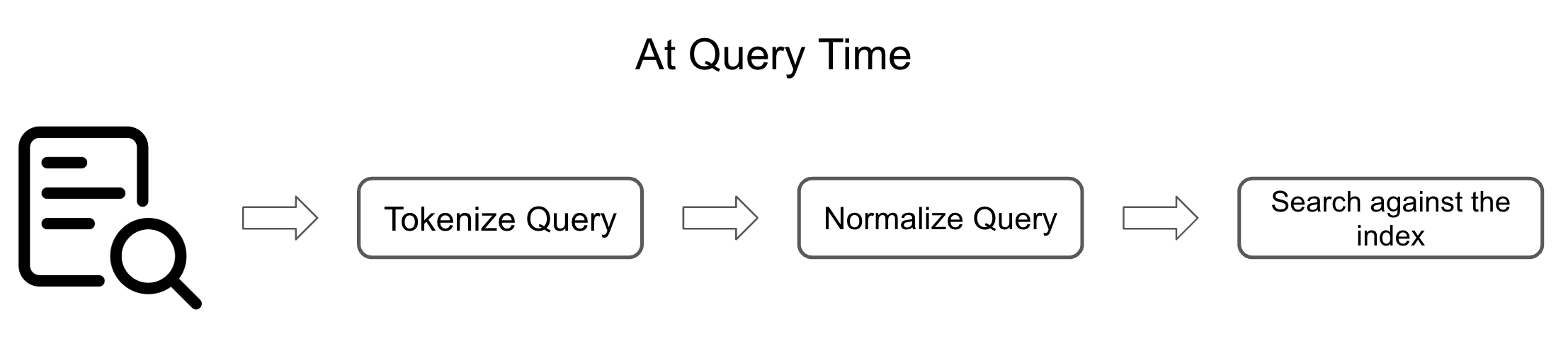

Consider two documents: “Kicking the round leather with friends improves mental health” and “Backstreet Boys are a music group.”

After preprocessing, the documents will have something like the following:

Document 0 - [“kick”, “the”, “round”, “leather”, “with”, “friend”, “improve”, “mental”, “health”]

Document 1 - [“backstreet”, “boy”, “be”, “a”, “music”, “group”]

Then the inverted index will look like:

{“kick”: [0], “the”: [0], “round”: [0], “leather”: [0], “with”: [0], “friend”: [0], “improve”: [0], “mental”: [0], “health”: [0], “backstreet”: [1], “boy”: [1], “be”: [1], “a”: [1], “music”: [1], “group”: [1]}

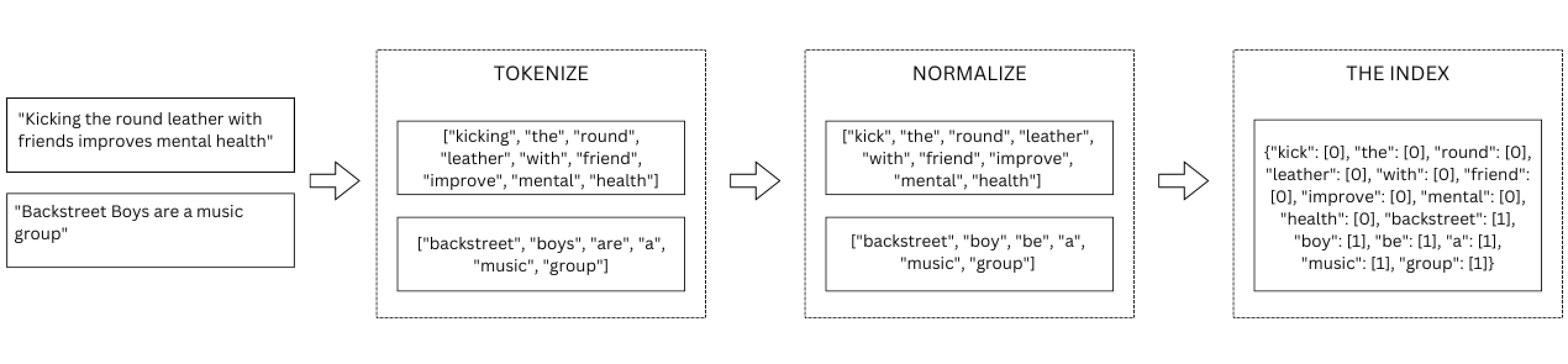

Given a search query, “I am so happy that my boys and I will play football today; I am excited,” let’s process a retrieval request.

The first step will be to tokenize the query, which gives:

[“i”, “be”, “so”, “happy”, “that”, “my”, “boy”, “and”, “i”, “will”, “play”, “football”, “today”, “i”, “be”, “excite”]

In this situation, none of the values in the query appear in document 0, while the values [“be”, “be”, “boy”] appear in document 1, leading to a score of 0 for the former and a score of 3 for the latter.

In essence, lexical search here says that document 1 is more relevant than document 0, but anyone with some understanding of the English language can see that document 0 is more relevant. There is a similarity between “round leather” and “football”, “I am so happy” and “improves mental health”, even if the words do not match.

Lexical search is fast, cost-efficient, and reasonably good at extracting relevant documents. However, it struggles with the absence of exact keywords.

If you want to learn more about the fundamentals of information retrieval, you can take the Text Retrieval and Search Engines course on Coursera. Do note that it is quite theoretical, but I took it a couple of years ago, and I still find myself going back to some of my notes every now and then. Really good stuff.

What is Semantic Search?

Next, I talk about semantic search. While lexical search is dependent on the presence of keywords, semantic search attempts to understand the meaning of text and use that understanding as a means of finding relevant documents.

Semantic search implementations can vary, but the most common approach is to rely on the vector space model using dense vectors to convey meaning in text. These dense vectors, or embeddings as they are commonly called, are often gotten from transformer encoders, which “somehow” manage to convert text into numbers. Many articles on the internet do a better job of explaining how transformer models work, so you can get a thorough understanding of encoders using those resources.

Like in lexical search, there are also some preprocessing transforms used in semantic search. However, such transforms are considerably different from the kind you do in lexical search; they mainly help the models convert text to embeddings.

The gist with semantic search is that text embeddings contain contextual information, and it is useful enough to rely on the similarity between embeddings as a measure of relevance.

Going back to the earlier example, we had:

Query: “I am so happy that my boys and I will play football today; I am excited.”

Document 0: “Kicking the round leather with friends improves mental health.”

Document 1: “Backstreet Boys are a music group.”

Adding one more document that would also have had a zero score in lexical search,

Document 2: “The sun is up guys, we can have soccer sessions, woohoo!!!”

Using the sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 as an embedding model, I get embeddings that look something like:

Query:

[-0.01294223, -0.01123377, 0.00591772, -0.10435747, 0.03420463, …]

Document 0:

[0.06874192, 0.1199687, 0.05535591, 0.0141326, -0.01607886, …]

Document 1:

[-0.00164266, -0.058489, -0.01499688, -0.00426761, 0.00169406, …]

Document 2:

[0.01470442, 0.03317017, 0.00964091, 0.03046494, 0.05122278, …]

Only the first 5 dimensions are printed, but the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model returns 384 embeddings. The numbers make no sense when you look at them, but if you visualize them, it makes more sense.

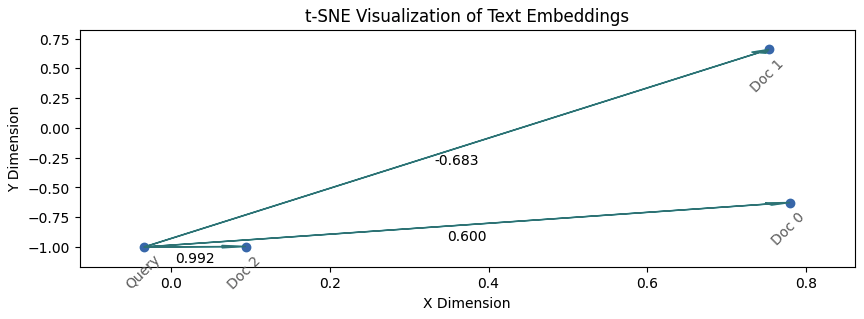

The illustration above visualizes the position of the query and documents in embedding space, where the edge labels are cosine similarity scores of the embeddings. Cosine similarity goes from -1 to 1, and the assumption is that documents with a score close to 1 are relevant.

The illustration shows that the embeddings are able to carry information about the context in text without a need for keyword dependence. In this case, Query is most relevant to Doc 2, with which it shares zero keywords, and least relevant to Doc 1, with which it shares the most number of keywords in the corpus.

NB: The embeddings were originally with 384 dimensions, but I reduced them to 2 dimensions using t-SNE to make it easier to visualize.

There is a lot more to semantic search than I have described in this section; the objective was to simply provide some context as to why it is considered an improvement on lexical search. Huggingface has a section on Semantic search with FAISS from their NLP course that does a better job of explaining the concepts than I have done in this section.

What is an In-memory Database?

On-disk databases are quite popular, from PostgreSQL to MongoDB, but Ahnlich is taking the model of storing data in-memory instead. There are a couple of implications that come with this decision, and this section looks to cover them.

On the positive side (for in-memory):

- The data is much faster to retrieve since expensive disk reads are not necessary for access. This implies lower latency for real-time use cases.

- Horizontal scaling is faster and less complex for in-memory databases when compared to disk-based databases.

- Concurrent requests can truly excel as they do not encounter the bottlenecks that occur when trying to read from disk.

On the negative side (against in-memory):

- The memory is more expensive than disk, so for a large index, running an in-memory database is costlier.

- Properly persisting an in-memory database requires deliberate effort, as disruptions to the running instance—such as crashes or restarts—can lead to data loss.

- If you are also storing some data in a main database, you need to manage the overhead that comes with keeping both in sync.

Side Note: On the topic of speed, you can go through this Stack Exchange explanation of why memory (RAM) is faster than storage to learn more.

Given these implications, an in-memory database is an excellent choice when speed is a priority. Vector search is one such example, as it involves complex calculations and multiple steps where speed is critical. An in-memory database is also a good option to use when looking to lift the workload of data retrieval from the actual database, using the in-memory database as a cache such that the main database is only queried if there is a cache miss.

Some examples of where this works:

Analytics Software: If you are building an analytics software that often processes a lot of compute-heavy queries and has significantly more frequent reads than writes, you don’t want to run all queries directly against the database. You can store computed results from queries in an in-memory database, such that the results are pulled quickly from there if the same query comes in again, relieving the database of the workload.

Recommendation Systems: If you are building a recommendation system and you have user embeddings and content embeddings. In this situation, you can keep the embeddings for the content in memory as well as the embeddings for active users; this way, you can compute content to show to the users without the latency that will come from disk reads.

There are many other use cases and approaches to using an in-memory database, so you need to think about your context when deciding if and how to use one.

Now that I have given some context on semantic search and in-memory databases, let’s talk about Ahnlich.

What is Ahnlich?

Putting together the concepts of an in-memory database and vector search, Ahnlich is a suite of tools built to make it easy for developers to integrate semantic search functionalities in their applications. This is without having to do the amount of work needed to properly integrate semantic search, such as doing the preprocessing, postprocessing, and finding the most similar data points.

It is made up of a couple of components:

- The Database

- The AI Service

- The CLI

- Language Clients: Rust and Python

The Database

This is the part of Ahnlich that stores data; one can consider it to be the most integral part of the whole setup. The database is responsible for saving the data, and it also makes it possible to run the search queries. One can also use the database without having vectors, in which case data access will be via the metadata passed in at indexing time. With the metadata-only setup, Ahnlich would function similarly to Redis.

The AI Service

Ahnlich’s AI service helps convert data into embeddings. The embeddings are expected to hold some form of meaning, such that one can make an assumption that two vectors that are close in the domain have similar meanings. The AI service leverages the ONNX runtime and Huggingface Hub to facilitate the conversion of data from the multimodal format into embeddings. There are a couple of models available, from the popular sentence transformers AllMiniLM models for generating sentence embeddings, to the CLIP models for image and text embeddings.

The CLI

This is the part of Ahnlich that makes it possible to run queries from the terminal or command prompt. With the CLI service, you can easily create an index, run test queries, and look into your setup without requiring an actual language client. The CLI can also be an avenue to learn more about the various features offered by Ahnlich and perform administrative tasks, all this without having to write any code. However, if you want to use Ahnlich within code, you should use the language clients.

Language Clients: Rust and Python

The Language Clients serve as a window through which you can access the database and AI service as you would via the CLI, but more natively, through the language of your choice. The language clients that Ahnlich currently provides are Rust and Python; however, there are plans to make it accessible in more languages so it can be used across various language stacks.

Why Build Ahnlich?

Ahnlich is not the first technology that exists to provide semantic search functionality. A lot of tools exist; some are specifically built to serve vector search use cases, and some provide great lexical search abilities to go with vector search (an approach referred to as hybrid search).

So why build Ahnlich if something exists?

I have a couple of answers:

- Curiosity and Learning

- Providing Model Integration

- Obsessed with Better

Curiosity and Learning

What does one need to know to build a vector database? What constraints are involved in building one? What languages are best suited?

These are some of the questions serving as internal motivating factors for us to get involved in building Ahnlich. Considering that none of us has built something of this kind before, it also served as a means to learn whatever was needed to achieve it. For me personally, I was looking to get involved in a team doing Rust stuff at work. I had also been doing some vector database work, so it was a good opportunity to learn something cool and also look deeper into the inner workings of the tech I use.

Providing Model Integration

Many vector databases are simply a means of storing embeddings; this means you as a user will have to find your own way to get the embeddings. You can either get the embeddings via third-party providers who expose APIs to their models or by self-hosting your models. In the case of Ahnlich, we wanted to make it possible for users who want to stick to on-device models, i.e., self-hosting, without having to do the work of setting up inference. Hence, one of the reasons Ahlich is a suite of tools, not just a database.

Obsessed with Better

This is more of a hope, but we are wondering what we can do better in terms of user experience when working with vector databases. In order to do this, we will need to get concrete feedback from users, which can be you. So we need you to use Ahnlich in your side projects and give us feedback on how you want it to be improved upon. As we get to work on the project into the next year, there will be a lot of use cases coming up, and we will be able to work on those and provide a better experience.

What is Next?

There are a couple of things we are looking to do now that we are done with the initial alpha release. Doing everything on this list does not mean the project is done; it just means it will be one step in the direction we want to go.

- Make it production ready: Ahnlich currently works, but it is not where we want it to be in terms of stability. Improving the error logs, testing it at a larger scale, optimizing the slow parts that we notice after profiling, etc. Getting these changes in will gradually move us towards a point where we can be confident that Ahnlich is ready to be used for production use cases.

- Provide a more Pythonic interface: Python is a very popular language, so it won’t be surprising if Python becomes the most common Ahnlich client. The challenge with the client is that we use serde_generate to compile it from Rust, but this is not outputting Pythonic code. Hence, the experience is not the most suitable for Python developers. We need to write a Python wrapper that helps us achieve this objective, where the wrapper’s main job is to give users the Pythonic feel, and we don’t write functionality into the wrapper. We intend to use gRPC to achieve this.

- Support a broader range of multimodal data: Images and text are the only kinds of data for which we support conversion into embeddings. However, there are many other kinds of multimodal use cases that we would like to cover, such as audio, video, or even stuff like time series data.

My Ask

The original purpose of me writing this piece was to share what I have been working on for the last couple of months and also share some of the things I learned while working on it. This is similar to how I shared my learnings from working on a trading system sometime last year, even though I did not get to write all the articles I hoped to write.

This time around, I will be writing only three articles about my learnings, and I hope I have the bandwidth to do it this time. The titles will be something in the line of:

- How I Built an Embedding Service in Rust

- Building An Embedding Service: Sharing My Three Surprises

- How to Debug your Embeddings

I will also be asking for two favors; my friends and I would appreciate it if you:

- Help give us a star on Github.

- Spend some time using Ahnlich in your side projects (it will be a slight deviation from what you already use, I know, I know), but your feedback will help us see what we have done well or wrongly. Any kind of feedback will be appreciated, from using it in an actual project to raising an issue on a bug you experience.

If you have read up till this point, thank you very much. Now I have to go and write the articles I have made a commitment to put into the world.

Leave a comment